About the Forgotten Children Initiative

This initiative is dedicated to honoring the memory of incarcerated youth buried in abandoned and lost burial grounds throughout the United States. The work was inspired by the recent discovery of nearly 250 incarcerated Black children who died at the Maryland House of Reformation & Instruction for Colored Children and were buried nearby between 1877-1939, most of whom were placed in unmarked graves.

About Maryland’s Lost Burial Ground

In 2023, the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services (DJS) initiated an effort to research and document the history of the agency and the state’s juvenile justice system, including its segregationist practices dating to the 1800s. Through archival research DJS documented racially segregated facilities, labor exploitation and physical abuses of incarcerated youth, and operational deficiencies and inequities at what was known as the House of Reformation and Instruction for Colored Children, a Blacks-only youth prison. DJS currently operates the successor facility to the House of Reformation, called the Cheltenham Youth Detention Center.

Legally established in 1870, the House of Reformation in Cheltenham, MD was the first reform school for delinquent Black children in the American South. Prior to its opening, Black youth, some as young as five years old, were being sent to adult jails and prisons for criminal offenses, delinquent acts and even status offender behavior such as running away from home. Admitting its first children in 1873, the House of Reformation opened two decades after the House of Refuge for Juvenile Delinquents– the reform school for delinquent white children which was established to remove white children from Maryland’s adult jails and prisons.

Through conversations DJS leadership had with a former DJS staff member who had worked at Cheltenham for over 40 years (and whose father had worked there for 40 years before him), it was learned that children who had died at the facility had been buried in an area adjacent to the House of Reformation. Subsequent research and on-site exploration confirmed the existence of the burial site.

An Obituary for Samuel Folks

The earliest known acknowledgment of the burial site is from an obituary for Samuel Folks, a boy who died at the House of Reformation in March, 1885. The obituary reads, “he was buried at the institution,” with a tombstone bearing his name and date of death. The cemetery was reported on again in a 1934 issue of The Afro-American newspaper in Baltimore. In that article, Harry Brown, a man who escaped from the House of Reformation as a child, confirmed the cemetery’s existence. He said that he helped conduct some of the burials, and that he knew “of no effort to embalm the bodies or to notify parents or guardians of the boys’ deaths.”

He also stated, “on one occasion… parents came to inquire about a boy, and were told that the boy had run away; but the truth is that I had helped bury the boy just the night before.”

MD Delegate Troy Brailey visiting House of Reformation burial site

Cinder Blocks for Graves

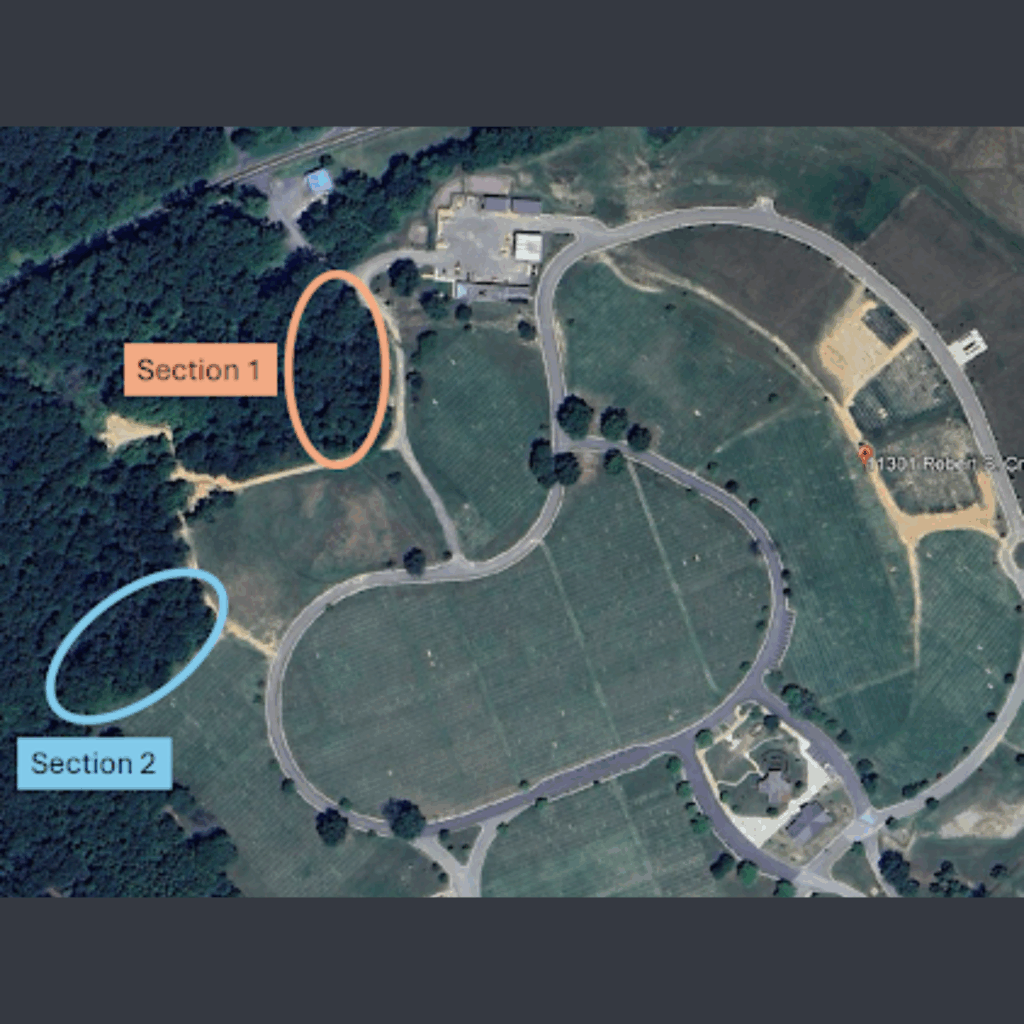

With the assistance of the Maryland Historical Trust, including locating maps from a survey conducted in 2009, DJS was able to rediscover the burial site in October 2024. The maps revealed that the burial ground has at least two sections, each in heavily wooded areas adjacent to an official and well-maintained cemetery for Maryland veterans operated by Maryland’s Department of Veterans and Military Affairs (DVMF).

The first section dates from the late 19th century and has five headstones that mark the burials of named boys ranging in age from 11 to 21 years old who had died between 1885 and 1888. The second section identified in the maps and located by DJS staff is believed to date from the early 20th century and contains rows of cinder blocks that mark the graves of House of Reformation youth with no identifying information. Surveyors in 2009 estimated that there were approximately 100 cinder block markers.

Children as Inmates

In addition to the headstones, through information on the “Find a Grave” website (an on-line database owned by Ancestry.com containing cemetery records from around the world), DJS was initially able to catalog the death certificates and obituaries of at least 80 youth who died at the House of Reformation and are likely buried in the burial site. The agency was able to track each youth’s age, county of origin, official cause of death, and parental information. The death certificates almost exclusively refer to incarcerated Black boys as “inmates” and allude to the forced labor that they endured, with many listing “broom shop” and “factory” in the “Occupation” section. Almost all of the death certificates list a disease as the official cause of death, though some also list things like “brick” and “stabbing”. The most common diseases listed are tuberculosis, pneumonia, typhoid fever, and meningitis. If accurate, this reflects the poor healthcare infrastructure at the House of Reformation, as the facility often lacked medical staff. However, it should not be assumed that the reform school administrators were always truthful about how these children died and news reporting from the time documents deaths that were the result of extreme abuse and neglect.

The Work Continues

The existence of the burial ground was publicly announced on July 17, 2025 during a visit to the cemetery by Maryland State Senator Will Smith (Chair of the Maryland Senate’s Judicial Proceedings Committee), Vinny Schiraldi (former DJS Secretary) and Marc Schindler (former DJS Assistant Secretary & Chief of Staff). During the announcement of the existence of the burial ground, Senator Smith also announced that he would be re-filing legislation to reduce the number of youth prosecuted in Maryland’s adult criminal justice system and that he would be holding hearings about the burial ground and the segregationist history of the state’s juvenile justice system.